The Federal League: 1876

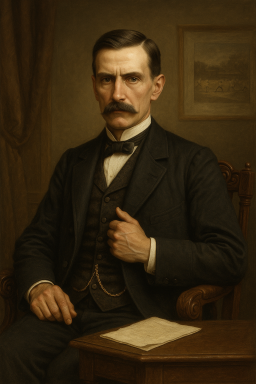

When Charles W. Garrison summoned his fellow magnates to a smoky Chicago parlor in the winter of 1875–76, professional base ball stood on unsteady ground. The old National Association, loose in its rules and lawless in its conduct, had become a byword for crooked play and crumbling finances. Garrison, proprietor of the Chicago Base Ball Club, had grown tired of it. “Order must replace chaos,” he was said to mutter, “or the game will belong to the gamblers, not the gentlemen.”

When Charles W. Garrison summoned his fellow magnates to a smoky Chicago parlor in the winter of 1875–76, professional base ball stood on unsteady ground. The old National Association, loose in its rules and lawless in its conduct, had become a byword for crooked play and crumbling finances. Garrison, proprietor of the Chicago Base Ball Club, had grown tired of it. “Order must replace chaos,” he was said to mutter, “or the game will belong to the gamblers, not the gentlemen.”

The Charter Clubs

The league launched with eight clubs:

-

Chicago Base Ball Club (Cyclones) — Garrison’s own side, sternly branded “Chicago” in the ledgers, but nicknamed by the press for their blustery style.

-

Philadelphia Centennials — owned by Henry C. Landis, a civic-minded lawyer determined to place his city at the game’s vanguard.

-

New York Knights — adopting chivalric airs to match Gotham’s self-regard.

-

Brooklyn Unions — tied to the borough’s workingmen’s clubs.

-

Detroit Woodwards — named for their Woodward Avenue grounds.

-

Cincinnati Monarchs — Bartholomew Fitch’s overreaching venture.

-

St. Louis Brewers — Adolph Fuchs’s blend of ball and beer garden.

-

Boston Pilgrims — Ezra Barzillai Whitcomb’s precarious bid to keep New England relevant.

On the Field

If Garrison demanded order in the boardroom, the season itself supplied drama enough. The Chicago Cyclones, powered by the remarkable right arm of Harry Taylor, stormed to the inaugural pennant with a record of 44–21. Taylor won every one of those victories, finishing with a 44–21 mark, a 2.33 earned run average, and even contributed a .343 average at the plate.

Chicago’s offense was anchored by second baseman Flint Jackson, who batted .379 to claim the league’s first batting crown. Philadelphia’s Ulysses Burke pushed him close at .352, while his team-mate, the versatile Patrick Johann “Factotum” Manke (.327 with a league-best 32 walks) revealed himself as a star in the making, a multi-positional marvel whose Irish and German parentage seemed a perfect emblem of base ball’s immigrant roots.

In New York, young pitcher Gus Murphy dazzled the cranks, compiling a 2.03 ERA to lead the league, even as his Knights fell short of Chicago’s pace. Detroit and Brooklyn scrapped respectably, while Cincinnati and St. Louis lurked in the lower half of the table, their mediocrity on the diamond mirrored by unreliability off it.

Final Standings, 1876

| Team | W | L | WPct | GB | R | RA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicago Base Ball Club | 44 | 21 | .677 | — | 462 | 312 |

| Philadelphia Centennials | 41 | 23 | .641 | 2½ | 391 | 276 |

| New York Knights | 40 | 29 | .580 | 6 | 392 | 288 |

| Brooklyn Unions | 34 | 32 | .515 | 10½ | 298 | 402 |

| Detroit Woodwards | 32 | 37 | .464 | 14 | 283 | 318 |

| Cincinnati Monarchs | 22 | 35 | .386 | 18 | 287 | 305 |

| St. Louis Brewers | 23 | 37 | .383 | 18½ | 302 | 372 |

| Boston Pilgrims | 24 | 46 | .343 | 22½ | 266 | 408 |

Discipline and Dissension

The standings told only part of the story. Cincinnati’s Fitch balked at the expense of eastern travel, and St. Louis’s Fuchs found more profit in lager than in league fixtures. When both clubs refused to complete their road trips to Philadelphia, New York, Brooklyn, and Boston, Garrison enforced the constitution with ruthless clarity: the Monarchs and Brewers were expelled.

Critics branded the expulsions tyrannical; supporters hailed them as proof the Federal League meant business. Either way, Garrison had drawn his line in the sand.

A Confusion of Names

Ironically, even as the league office insisted on order, its clubs flirted with chaos in identity. Newspapers christened and rechristened them at will: by 1877 the Centennials would become the Unions, the Unions would adopt the Athletics, the Knights would emerge as the Columbians, and the Pilgrims would stumble on as the Resolutes.

To the cranks in the stands, it scarcely mattered; they came to jeer, cheer, and wager. But to Garrison, the confusion was an ever-present reminder that discipline on paper could not tame the anarchy of public fancy.