- Details

- Category: Baseball

1887 Season Recap

Records & Rivalries

The 1887 season rewrote the record books. From Conn Bolick’s thunderous 28 home runs to Charlie Shanafelt’s (shown left) slugging feats and John Tennison’s barrage of runs and RBIs, the game tilted toward offense like never before. Isaac Montgomery piled up hits, Dave Dye raced into the stolen base record, and Buster Brown delivered the finest all-around season yet measured. At the same time, rivalries burned hotter — St. Louis versus Louisville for supremacy, the IA’s Pilots and Tigers trading blows, and even New York’s Barons overshadowing their struggling Excelsior cousins. It was a year of gaudy numbers and fierce contests, a turning point in the young sport’s history.

Offseason Recap

The winter of 1886–87 once again shuffled the base ball map:

-

Pittsburgh Vulcans Join the Federal League: Pittsburgh crossed over from the International Association, replacing Barclay’s folded St. Louis Pioneers.

-

Indianapolis Westerners Replace Kansas City: A fire consumed Kansas City’s wooden ballpark, and when the city refused to pay damages, the club moved to Indianapolis. Most of the roster was sold off to finance the shift, leaving a barebones side to limp through 1887. The city agreed to co-finance a new park, paving the way for a return in 1888, until....

-

Corn Belt League Formed: A new minor circuit, with Lincoln and Peoria tying for the pennant. The league also kept Kansas City active with a club during the city’s (purported) one-year absence from top-flight play.

-

A New Voice in Louisville: Twenty-three-year-old newspaperman Harry Thorne began covering the Colts and befriended slugger Larry Buckley. Thorne railed against rowdyism, gambling, and crookedness, calling for “clean base ball.” Few noticed then, but some believe Thorne’s crusading spirit may one day change the game itself.

Federal League

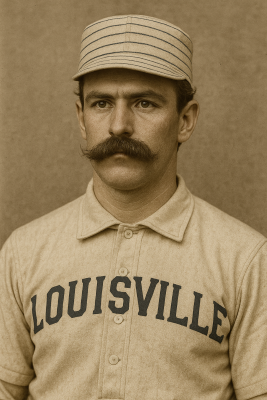

The Louisville Colts (86–40, .683) seized the flag in a season dominated by longball fireworks. Larry Buckley (.354, 125 RBIs) and Charlie Shanafelt (23 HR, .365) formed the most feared duo in the league, though Chicago’s Conn Bolick stole the headlines with a record 28 home runs, shattering all precedent.

Detroit’s Bill Poole carried the Sturgeons with a 39-win season, while Philadelphia’s Thomas Goss added a string of memorable pitching gems. Pittsburgh’s Federal debut was respectable, but Indianapolis and Washington floundered, both losing over 90 games.

Federal League Standings (1887)

| Team | W | L | Pct | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Louisville Colts | 86 | 40 | .683 | — |

| Detroit Sturgeons | 83 | 46 | .643 | 4.5 |

| Chicago Cyclones | 80 | 48 | .625 | 7.0 |

| Pittsburgh Vulcans | 59 | 68 | .465 | 27.5 |

| Philadelphia Unions | 55 | 70 | .440 | 30.5 |

| New York Barons | 52 | 75 | .409 | 34.5 |

| Indianapolis Westerners | 47 | 79 | .373 | 39.0 |

| Washington Federals | 45 | 81 | .357 | 41.0 |

International Association

The St. Louis Pilots became the first IA club to crack 100 wins, finishing 100–37 (.730) and outdistancing Montreal by 14 games. Their twin aces — Zebulon Eldridge (41 wins) and Ajax McFadden (38 wins, 2.47 ERA) — dominated the league, while John Tennison set a new IA record with 142 RBIs.

Toronto’s Isaac Montgomery repeated as batting champion, hitting .380 with a record 219 hits, and teammate Glen Nalley fanned 185 batters in his sophomore season. Montreal’s Spider Burchett (.310) again provided steady hitting, but the Tigers fell short.

Cleveland’s Clippers struggled badly in their debut, going 45–88, while the once-proud New York Excelsiors hit bottom at 46–92.

International Association Standings (1887)

| Team | W | L | Pct | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Louis Pilots | 100 | 37 | .730 | — |

| Montreal Tigers | 87 | 52 | .626 | 14.0 |

| Toronto Provincials | 71 | 67 | .514 | 29.5 |

| Baltimore Bannermen | 71 | 70 | .504 | 31.0 |

| Boston Brahmins | 66 | 72 | .478 | 34.5 |

| Cincinnati Monarchs | 64 | 72 | .471 | 35.5 |

| Cleveland Clippers | 45 | 88 | .338 | 53.0 |

| New York Excelsiors | 46 | 92 | .333 | 54.5 |

World Championship Series

The second World Championship Series saw the IA’s St. Louis Pilots face the Federal champion Colts. It was a closely fought affair, but the Pilots prevailed 4–2 behind Tennison’s bat and Eldridge’s steadiness. Louisville manager Larry Buckley conceded: “We will be working on fundamentals a lot next spring.”

The triumph came in the aftermath of St. Louis’s third IA pennant in four years, cementing their dynasty and placing the IA on equal footing with the senior Federal loop.

Minor League Highlights

-

Eastern Association: Albany (81–31) repeated as champions, powered by Virgil Pendergrast (.383) and Bob Joy (38 wins, 440 Ks).

-

Corn Belt League: Lincoln and Peoria tied at 82–30, with Peoria’s Guy Byram (.348) and Lincoln’s Marty Flicka (14 HR, 85 RBIs) starring.

-

Southern States League: Atlanta and Birmingham tied at 64–48. Atlanta’s Jim Duffee (33 wins, 405 Ks) and Dave Tuttle (.362, 13 HR) defined the league’s third campaign.

Notable Performances

-

Conn Bolick (Chicago) – record 28 home runs, shattering the previous mark.

-

Charlie Shanafelt (Louisville) – hit 23 homers, plus a league-leading .616 slugging percentage.

-

Isaac Montgomery (Toronto) – hit .380 with 219 hits, solidifying his star power.

-

John Tennison (St. Louis) – record 142 RBIs, centerpiece of the Pilots’ title run.

-

Zebulon Eldridge (St. Louis) – won 41 games, leading a devastating staff.

-

Bill Poole (Detroit) – posted 39 wins at age 20, already a cornerstone.

-

Martin Bird (New York Barons) – threw 17 innings with 15 Ks in the year’s top pitching feat.

-

Larry Buckley (Louisville) – had two 6-for-6 games, driving in eight in one outing.

-

Dave Dye (Philadelphia) – stole a record 91 bases, ushering in the stolen base era.

-

Buster Brown (Montreal) – delivered a record 9.39 WAR, the most complete season yet.

Trouble in New York

Amid the glory elsewhere, the New York Excelsiors teetered on collapse. Crushed financially and consistently outdrawn by the Federal League’s Barons, they staggered to a 46–92 finish. Rumors swirled of contraction or replacement, with even their owner Jeremiah Goodwin hinting at “difficult decisions” to come.

⚾ 1887 was the year of Records & Rivalries — a season that expanded the game’s horizons, crowned a dynasty in St. Louis, and introduced a new power-driven style that would define the years ahead.

- Details

- Category: Baseball

1886 Season Recap

Offseason Recap

The winter between 1885 and 1886 brought both upheaval and innovation.

League and Team Changes

The Federal League carried out a major reshuffling. The Cleveland Blue Caps and Rochester Robins, both beset by empty coffers, were removed. In their place came two fresh entries: the Washington Federals and the Kansas City Westerners. The circuit remained at eight clubs, but the new alignment hinted at both geographic ambition and a willingness to jettison tradition.

The International Association, by contrast, stood pat. Its lineup of eight remained unchanged, and this stability was trumpeted as proof of its legitimacy in the face of Federal turbulence.

Rule Changes

Both leagues tinkered with the rulebook.

-

Walks: In the IA, a walk was trimmed to six balls (down from eight). In the FL, it was raised to seven (from six). The difference remained a sore point.

-

Stolen Bases: Now counted as an official statistic, heralding a new weapon for speedy men on the basepaths.

-

Pitcher’s Box: Extended by one foot toward second base, another small step toward reshaping the pitcher–batter duel.

-

Schedule: Expanded again — the FL from 112 to 126 games, the IA from 112 to 140.

Business Shifts

Admission pricing became a battlefield. The FL relented in Philadelphia and St. Louis, allowing 25-cent tickets in response to the IA’s bargain strategy. Everywhere else, 50 cents remained the standard. Owners grumbled, but the cranks came, and that was what mattered.

Federal League

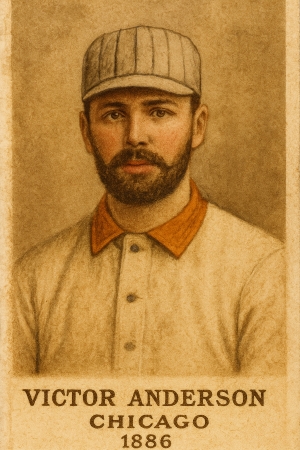

The Chicago Cyclones stormed to their first flag since 1877, obliterating the competition with an 87–31 record (.737). Their ace, Victor Anderson, turned in one of the greatest seasons yet seen: 54 wins, a 1.79 ERA, and 352 strikeouts, capped by his starring role in the postseason.

The Chicago Cyclones stormed to their first flag since 1877, obliterating the competition with an 87–31 record (.737). Their ace, Victor Anderson, turned in one of the greatest seasons yet seen: 54 wins, a 1.79 ERA, and 352 strikeouts, capped by his starring role in the postseason.

Louisville rode the bat of Larry Buckley, who defected from Rochester and instantly justified the move. Buckley’s line — .382, 16 home runs, 134 RBIs — was a tour de force, pairing with Charlie Shanafelt (.303, 15 HR, 116 RBI) to make the Colts dangerous, though not enough to catch Chicago.

Philadelphia and St. Louis both hovered in the first division, while Kansas City showed flashes in its debut. The New York Barons slumped, Detroit remained middling, and Washington’s entry was a catastrophe, staggering to a 34–94 record.

Federal League Standings (1886)

| Team | W | L | Pct | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicago Cyclones | 87 | 31 | .737 | — |

| Louisville Colts | 75 | 51 | .595 | 12.0 |

| Philadelphia Unions | 69 | 60 | .535 | 18.5 |

| St. Louis Pioneers | 60 | 66 | .476 | 27.0 |

| Kansas City Westerners | 59 | 66 | .472 | 27.5 |

| New York Barons | 57 | 70 | .449 | 33.0 |

| Detroit Sturgeons | 56 | 70 | .444 | 33.5 |

| Washington Federals | 34 | 94 | .266 | 59.5 |

International Association

The St. Louis Pilots repeated, edging Montreal in a thrilling pennant race. Their 90–50 record (.643) was powered by Ajax McFadden (38–22, 2.22 ERA) and Bulldog Ayers (30–13, 2.70 ERA), a formidable one-two punch.

Montreal’s Spider Burchett emerged as a rising star, batting .310 with 99 RBIs, while Toronto’s Isaac Montgomery remained the IA’s brightest light, hitting .370 with 87 RBIs. His teammate, Glen Nalley, just 22 years old, struck out 461 batters, cementing his place as the most electrifying young pitcher in the game.

Elsewhere, the Bannermen and Excelsiors recovered respectably, Pittsburgh hovered near .500, while Cincinnati and Boston sank to the cellar. The Brahmins, once heralded as the IA’s salvation in Boston, staggered to 43–98, raising uncomfortable questions about the city’s appetite for two major clubs.

International Association Standings (1886)

| Team | W | L | Pct | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Louis Pilots | 90 | 50 | .643 | — |

| Montreal Tigers | 88 | 52 | .628 | 2.0 |

| Baltimore Bannermen | 72 | 67 | .518 | 17.5 |

| New York Excelsiors | 71 | 66 | .518 | 17.5 |

| Toronto Provincials | 71 | 68 | .511 | 18.5 |

| Pittsburgh Vulcans | 69 | 70 | .496 | 20.5 |

| Cincinnati Monarchs | 53 | 88 | .376 | 37.5 |

| Boston Brahmins | 43 | 98 | .305 | 47.5 |

The Inaugural World Championship Series

At long last, the question of supremacy was answered on the field. The Chicago Cyclones (Federal champions) met the St. Louis Pilots (IA champions) in St. Louis for the inaugural World Championship Series.

What promised drama became a rout. Chicago swept the Pilots in four straight games, with Victor Anderson the unchallenged hero. His iron arm carried the Cyclones to history’s first official World Championship, confirming the Federal League’s claim as the senior circuit.

Still, the Series drew strong crowds and raucous headlines, its success ensuring it would become an annual tradition. For the first time, base ball had not just league champions — but a world champion.

⭐ Notable Performers of 1886

-

Larry Buckley, 1B, Louisville Colts – Hit .382 with 16 HR and 134 RBIs, the most complete offensive season yet recorded.

-

Victor Anderson, P, Chicago Cyclones – 54–15, 1.79 ERA, 352 Ks; capped it with a World Series MVP.

-

Isaac Montgomery, CF, Toronto Provincials – .370 average with 87 RBIs; a star in the making.

-

Ajax McFadden, P, St. Louis Pilots – 38 wins, 2.22 ERA; ace of the champions.

-

Spider Burchett, RF, Montreal Tigers – .310 average, 99 RBIs; at just 23, a cornerstone for years to come.

-

Glen Nalley, P, Toronto Provincials – 461 Ks at age 22, redefining the strikeout.

-

Bulldog Ayers, P, St. Louis Pilots – Veteran anchor at 30–13, 2.70 ERA.

-

Charlie Shanafelt, RF, Louisville Colts – .303, 15 HR, 116 RBIs; a rising power hitter.

-

Spider Lamb, P, Pittsburgh Vulcans – 30 wins, 296 Ks; proof of Pittsburgh’s budding strength.

-

Bill Poole, P, Detroit Sturgeons – Only 20, with 253 Ks and a 2.94 ERA despite poor support.

⚾ The year 1886 gave base ball its first true world champion, a showcase of stars young and old, and the beginnings of a new style of play — faster on the bases, bolder on the mound, and sharper in the boardrooms.

- Details

- Category: Baseball

1885 Season Recap

Federal League

The Federal League enjoyed one of its most balanced seasons to date, with no juggernaut to rival Cleveland’s dominance of a year prior. Instead, parity reigned, and the New York Barons (67–45, .598) edged out Philadelphia and the new arrivals from St. Louis to claim the pennant.

The Federal League enjoyed one of its most balanced seasons to date, with no juggernaut to rival Cleveland’s dominance of a year prior. Instead, parity reigned, and the New York Barons (67–45, .598) edged out Philadelphia and the new arrivals from St. Louis to claim the pennant.

New York’s success rested on their arms: Doug Crockett (34 wins) and Martin Bird (32) kept the Barons in every contest. At the plate, Rochester’s Larry Buckley again made his mark, batting .326 to seize his second straight batting crown, adding 29 doubles and 11 home runs to cement his reputation as the league’s most dangerous hitter.

But if Buckley supplied consistency, Cleveland’s Will Wessels brought power, leading the league with 13 home runs. The Blue Caps, however, faltered badly after their 1884 triumph, finishing last at 45–68, undone by injuries and poor support behind ace Dan Hicks.

Federal League Standings (1885)

| Team | W | L | Pct | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New York Barons | 67 | 45 | .598 | — |

| Philadelphia Unions | 58 | 53 | .523 | 8.5 |

| St. Louis Pioneers | 57 | 54 | .514 | 9.5 |

| Chicago Cyclones | 57 | 56 | .504 | 10.5 |

| Louisville Colts | 54 | 54 | .500 | 11.0 |

| Rochester Robins | 53 | 55 | .491 | 12.0 |

| Detroit Sturgeons | 54 | 59 | .478 | 13.5 |

| Cleveland Blue Caps | 45 | 68 | .398 | 22.5 |

International Association

In the International circuit, St. Louis proved their Federal counterparts not the only ones to dominate. The Pilots (71–40, .640) captured the flag, fending off a spirited chase from the Montreal Tigers (70–42, .625).

Toronto’s Isaac Montgomery was the league’s sensation, batting a resounding .370 to capture the batting title, while also pacing the loop with 87 runs batted in. He was ably supported by teammate Glen Nalley, who led the IA with 318 strikeouts. Baltimore’s Tom Child (quickly snapped up when Quebec folded) claimed the wins crown with 38, while St. Louis Pilots ace Ajax McFadden posted 34 victories of his own.

Elsewhere, the Bannermen remained strong, Pittsburgh showed flashes, and the Excelsiors of New York endured a humiliating fall, finishing dead last at 39–69 after their star-crossed roster faltered.

International Association Standings (1885)

| Team | W | L | Pct | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Louis Pilots | 71 | 40 | .640 | — |

| Montreal Tigers | 70 | 42 | .625 | 1.5 |

| Toronto Provincials | 61 | 51 | .545 | 10.5 |

| Baltimore Bannermen | 60 | 50 | .545 | 10.5 |

| Pittsburgh Vulcans | 54 | 59 | .478 | 18.0 |

| Cincinnati Monarchs | 46 | 66 | .411 | 25.5 |

| Boston Brahmins | 44 | 68 | .393 | 27.5 |

| New York Excelsiors | 39 | 69 | .361 | 30.5 |

Beyond the Pennant Races

The year was notable for more than just championships. Two new minor circuits appeared on the map: the Southern States League, captured by Durham, and the Eastern Association, where Albany and Wilmington finished as co-champions at 42–28. Once-mighty Gus Murphy, the Irish ironman of New York, now plied his trade in the EA, battling back from the “dead arm” that had ruined him in 1883. His hope remained a return to the big time, though the odds seemed long.

Even more momentous was the stir among the players themselves. In Philadelphia, fiery Mike McCord rallied his Union teammates to form the Professional Base Ball Players Union, the first organized effort to secure leverage against the owners’ iron grip. Eight men signed their names, seeking freedom from the hated reserve clause and the threat of blacklisting. Owners responded by instituting a nominal $2,000 salary cap, though in practice no one paid it any heed. The lines between labor and management had been drawn, and though the union’s future was uncertain, the challenge had been made plain.

- Details

- Category: Baseball

Keeping the Stove Hot: Winter of 1884–85

The snow fell on a game in flux. The National Alliance had expired almost as quickly as it began, leaving behind only ashes — and two smoldering embers in Boston and St. Louis. With the Pioneers destined for survival, and whispers of Boston’s Brahmins seeking shelter elsewhere, attention turned to the two established leagues, both of which took decisive steps to prune their ranks and steady their course.

“Eight Shall Carry On” – The International Association Contracts

From the New York Herald, December 1884

From the New York Herald, December 1884

The International Association has survived its most ambitious year, but at a cost. Twelve clubs proved too many for the circuit to sustain, the talent spread thin and the patrons reluctant to fill the benches in lesser cities. At the annual winter meeting, the magnates acted decisively: four clubs will be struck from the rolls, leaving a more compact and competitive league of eight.

Foremost among the changes is the retention of Boston. The city’s Minutemen proved a dreadful failure, but fortune smiled when the champions of the late National Alliance, the Boston Brahmins, found themselves without a home. Their owner, Mr. Percival Whittemore (shown left), secured Boston’s slot in the International, merging the Brahmins’ roster and name into the Association. Thus, New England retains its pride, and the league gains not a liability but a pennant-winner.

Elsewhere, the Washington Legislators and Quebec Beavers are no more, their support too meager to warrant continuance. The Toledo Toms likewise vanish, squeezed out by larger neighbors.

Those remaining: St. Louis, Baltimore, Montreal, New York, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Toronto, and Boston, form the new backbone of the Association. Together, they vow to present a sterner competition in 1885, stripped of weaklings and wastrels.

Yet questions remain. With the Federal League absorbing St. Louis from the fallen National Alliance, and whispers that more realignments may come, the base ball world faces another season of intrigue. For now, the International claims eight strong clubs. Whether they remain so when the snow melts, only time will tell.

“The Strongest Eight” – Federal League Announces Contraction

From the Chicago Tribune, December 1884

The Federal League, the senior circuit of professional base ball, enters 1885 with a renewed sense of order and strength. At their winter conclave in Boston, the magnates resolved to trim their ranks to eight clubs, ensuring quality over quantity in the campaign to come.

The Milwaukee Creams, perennial stragglers, are no more. Despite earnest efforts, the Cream City failed to produce either the cranks or the coin to sustain top-flight base ball. Their departure was met with shrugs in most quarters, and sighs of relief in others.

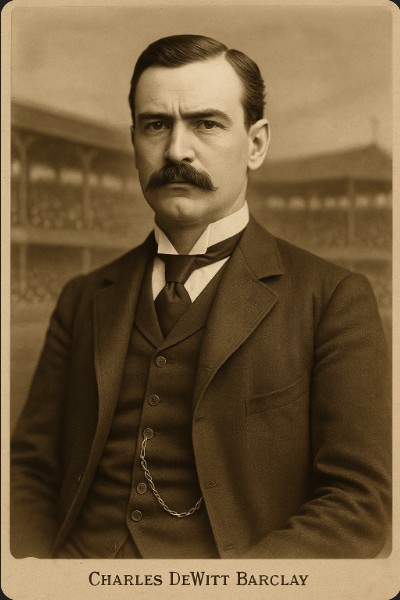

In their stead, the league looks westward with excitement. The St. Louis Pioneers, champions-in-waiting of the late National Alliance, arrive with full purses and great ambition. Under the stewardship of financier Charles DeWitt Barclay, the Pioneers promise to add luster (and no small controversy) to the Federal banner. Barclay’s determination to seat his club among the game’s aristocracy has already unsettled more cautious men, but none can deny that his Pioneers bring both pedigree and promise.

Thus the Federal League marches into its tenth season with these eight clubs: Cleveland, New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Rochester, Louisville, Detroit, and now St. Louis. A sturdy roster, drawn from the strongest cities and clubs, with no weak sisters to weigh down the schedule.

With Cleveland fresh off a glorious pennant, New York and Philadelphia resurgent, and St. Louis looming on the horizon, the stage is set for perhaps the most competitive season yet. The Federal League proclaims itself the standard-bearer of professional base ball — and dares any rival to say otherwise.

- Details

- Category: Baseball

1884 Season Recap

Federal League

Order held firm in the senior circuit, and the Blue Caps of Cleveland finally claimed the crown that had eluded them since 1879. Their talisman was pitcher Dan Hicks, whose season defied belief: 45 victories, a 2.01 ERA, and 363 strikeouts, good for the first true Pitching Triple Crown in Federal history. Hicks carried Cleveland to a 75–40 mark (.652), finishing comfortably ahead of New York and Philadelphia.

The bats were no less lively. Larry Buckley of Rochester seized the batting crown at .337 while driving in 96 runs and crossing the plate 113 times. Buckley’s blend of power (18 home runs) and consistency made him the most feared hitter in the league, though it was not enough to elevate the Robins beyond the middle of the pack.

New York’s Barons again found themselves bridesmaids, Philadelphia recovered from years of mediocrity, and Chicago’s Cyclones hovered near the first division. Detroit and Milwaukee sagged into the cellar, proving that even in a time of expansion and prosperity, not every market could sustain a winner.

Federal League Standings (1884)

| Team | W | L | Pct | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleveland Blue Caps | 75 | 40 | .652 | — |

| New York Barons | 70 | 45 | .609 | 5.0 |

| Philadelphia Unions | 63 | 52 | .548 | 12.0 |

| Chicago Cyclones | 58 | 50 | .537 | 13.5 |

| Rochester Robins | 56 | 59 | .487 | 19.0 |

| Louisville Colts | 48 | 66 | .421 | 26.5 |

| Detroit Sturgeons | 46 | 70 | .397 | 29.5 |

| Milwaukee Creams | 33 | 81 | .289 | 41.5 |

International Association

If Cleveland ruled the Federal, the IA’s banner went to St. Louis, where Adolph Fuchs’s Pilots soared to a 73–37 record (.664). Baltimore (70–38) pressed them all the way, but it was in St. Louis that fortune smiled longest.

The league’s batting laurels went to Curt Johnston of Baltimore, whose .353 average kept the Bannermen in the race. Yet the true thunder resided in New York: Jim “The Great Scot” Scott smashed 19 home runs and collected 107 runs batted in, both league highs, cementing the Excelsiors as the IA’s most glamorous draw.

Pitching honors were spread across the circuit. Albie Scott, having fled the collapsing National Alliance in midsummer, returned to his native Washington and promptly led the IA with a 1.81 ERA. Candy Lemmons of the Excelsiors won 40 games with a 1.82 ERA, while Indianapolis ace Stanley Lamb fanned 427, setting a strikeout standard that may endure for years.

Of the IA’s newcomers, Quebec and Toledo showed flashes of promise, while Washington’s Legislators and Boston’s Minutemen floundered badly, the latter propping up the table at 28–81. Still, the IA emerged stronger than it began, its footprint now stretching from the St. Lawrence to the Mississippi.

International Association Standings (1884)

| Team | W | L | Pct | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Louis Pilots | 73 | 37 | .664 | — |

| Baltimore Bannermen | 70 | 38 | .648 | 2.0 |

| Montreal Tigers | 69 | 40 | .633 | 3.5 |

| New York Excelsiors | 67 | 43 | .609 | 6.0 |

| Quebec Beavers | 57 | 51 | .528 | 15.0 |

| Pittsburgh Vulcans | 55 | 57 | .491 | 19.0 |

| Indianapolis Stars | 50 | 59 | .459 | 22.5 |

| Toledo Toms | 50 | 59 | .459 | 22.5 |

| Cincinnati Monarchs | 50 | 62 | .446 | 24.0 |

| Toronto Provincials | 39 | 70 | .358 | 33.5 |

| Washington Legislators | 38 | 72 | .345 | 35.0 |

| Boston Minutemen | 28 | 81 | .257 | 44.5 |

National Alliance

If the Federal and International Leagues embodied stability, the National Alliance proved the opposite. Formed with bluster and boasting eight clubs, it ended the year in tatters, reduced to six after Cincinnati folded on August 14 and Washington expired on September 1. The departures confirmed what many suspected from the outset: the Alliance was a house built on sand.

On the field, the one shining beacon was Boston, where the upstart Brahmins stormed to the pennant at 62–34 (.646). Their rookie ace Will James delivered one of the great debut campaigns in memory, winning 40 games while leading the league in strikeouts (458) and ERA (1.38). At the plate, Boston catcher Bob Marshall batted .351, led the league in home runs (12), and tied for the RBI crown with 55 — a rare feat of dominance at his position.

The league’s central drama, however, lay in St. Louis. Charles DeWitt Barclay, magnate, financier, and self-appointed NA President, stocked his Pioneers with stars lured from the wreckage of Washington in September. Even with the infusion of talent, the Pioneers fell short of Boston, finishing second at 55–37, but their outsized payroll and ambition ensured their survival. Already whispers circulated that Barclay’s club would not remain shackled to the flimsy Alliance.

Elsewhere, Philadelphia and Chicago muddled through, Baltimore drank more than it won, and Kansas City gamely pressed on despite financial woes. Cincinnati and Washington’s collapses sent many of their players scattering into the Federal and International circuits, further undermining the NA’s credibility. By season’s end, the Brahmins were champions in name, but it was clear the experiment had failed.

National Alliance Standings (1884)

| Team | W | L | Pct | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston Brahmins | 62 | 34 | .646 | — |

| St. Louis Pioneers | 55 | 37 | .580 | 7.0 |

| Philadelphia Bells | 45 | 48 | .484 | 17.5 |

| Chicago Catamounts | 51 | 46 | .526 | 11.5 |

| Baltimore Cannons | 42 | 49 | .461 | 19.5 |

| Kansas City Bulls | 41 | 45 | .477 | 18.0 |

| Washington Columbians | 33 | 48 | .407 | — folded Sept 1 |

| Cincinnati Dutchmen | 16 | 50 | .242 | — folded Aug 14 |

Keeping the Stove Hot

The winter of 1884 opened with more questions than answers. The National Alliance had plainly collapsed, its flimsy structure undone by unpaid wages, folding clubs, and a credibility gap too wide to bridge. Yet whispers abounded that not every Alliance nine would vanish into history.

The St. Louis Pioneers, flush with Charles DeWitt Barclay’s money and ambition, seemed destined for survival. Whether they would march straight into the Federal League, or attempt to cobble together a new circuit, remained the subject of endless speculation. Across the country, rumors swirled that the Boston Brahmins, champions in the Alliance’s only season, might yet find a home as well. Some claimed they would replace the feeble Boston Minutemen in the International Association; others thought their future tied to Barclay’s designs.

The IA itself faced hard choices. Twelve clubs had proven too many, diluting both talent and public enthusiasm. Crowds dwindled in smaller cities, and even the success of Baltimore and St. Louis could not mask the weakness elsewhere. Contraction back to eight seemed likely, but the question of who would survive the cut was left hanging in the winter air. Would Quebec be spared? Would Washington’s brief experiment be allowed to continue? Could Toledo and Indianapolis justify their places? None could say for certain.

Only one truth seemed beyond dispute: the National Alliance was finished. What form the great game would take in 1885, and who would be left standing to contest it, was left to rumor, ambition, and the turning of the new year.