- Details

- Category: Baseball

1883 Season Recap

Federal League

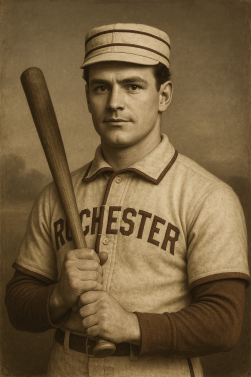

The Rochester Robins soared to the pennant, edging out the hard-charging Cleveland Blue Caps in an "extra game" after the clubs finished tied through 98 contests. Rochester’s 63–36 mark (.636) was built on steady pitching and the bat of Larry Buckley, who made history with the first batting Triple Crown in organized base ball: a .344 average, 10 home runs, and 95 runs batted in. Buckley’s totals were all league highs, with New York’s Dave Claiborne (.339) and Chicago’s ironman player-manager Morgan Cook (.333) close behind.

Federal League Standings (1883)

| Team | W | L | WPct | GB | R | RA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rochester Robins | 63 | 36 | .636 | — | 566 | 446 |

| Cleveland Blue Caps | 62 | 37 | .626 | 1 | 566 | 423 |

| Chicago Cyclones | 54 | 42 | .563 | 7½ | 532 | 484 |

| New York Columbians | 49 | 49 | .500 | 13½ | 516 | 476 |

| Louisville Colts | 47 | 51 | .480 | 15½ | 466 | 498 |

| Detroit Sturgeons | 39 | 58 | .402 | 23 | 454 | 573 |

| Philadelphia Unions | 39 | 59 | .398 | 23½ | 434 | 552 |

| Milwaukee Creams | 38 | 59 | .392 | 24 | 503 | 585 |

Though Buckley dominated headlines, the press remained curiously quiet about Louisville’s Sam Day, the Australian-born second baseman who continued to do everything well for a third straight year. Playing in relative obscurity for the mid-pack Colts, Day never received the plaudits his all-around play deserved.

On the mound, numbers were gaudier than elegant. New York’s Martin Bird took the ERA title at 2.34, while Chicago’s Doug Crockett claimed the wins crown with 39. The ironman laurels, however, belonged to a pair of pitchers who seemed almost superhuman. Philadelphia’s Mike McCord, discarded by Cleveland after a “dead arm,” rebounded with 61 starts for the Unions, going 21–36 across an eye-watering 504 innings. Yet even he was overshadowed by New York’s folk hero Tom “The Erie Eel” Ewart, who started 63 games on the mound and 35 more in center field. Ewart’s 28–34 record, 2.99 ERA, league-best 251 strikeouts, 58 complete games, and 4 shutouts, paired with a .286 batting average and solid glove in the outfield, made him the Columbians’ not-so-secret weapon and a fan favorite across the loop.

International Association

The Federal’s rival, the International Association, found its rhythm in 1883, thanks in no small part to the arrival of the long-dominant New York Excelsiors. Long a barnstorming juggernaut, the Excelsiors finally joined organized play and promptly ran off with the pennant at 61–37. Their arrival was controversial — owner Jeremiah Goodwin, a sharp-eyed businessman with little regard for collegiality, had poached liberally from both Federal and IA clubs in building his roster.

Independent Association Standings (1883)

| Team | W | L | WPct | GB | R | RA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New York Excelsiors | 61 | 37 | .622 | — | 525 | 434 |

| Pittsburgh Vulcans | 57 | 41 | .582 | 4 | 535 | 440 |

| Baltimore Bannermen | 56 | 42 | .571 | 5 | 539 | 443 |

| Montreal Tigers | 50 | 48 | .510 | 11 | 522 | 485 |

| Toronto Provincials | 49 | 49 | .500 | 12 | 538 | 518 |

| Indianapolis Stars | 44 | 54 | .449 | 17 | 450 | 530 |

| Cincinnati Monarchs | 42 | 56 | .429 | 19 | 462 | 555 |

| St. Louis Pilots | 33 | 65 | .337 | 28 | 395 | 561 |

His prize catch was Scottish-born first baseman Jim “The Great Scot” Scott, who lived up to his nickname by hitting .353 with 29 doubles, 12 triples, and 75 runs batted in. Alongside him was Paul Weyman, the league’s lone Black player and a versatile defender who could also take the mound. Weyman’s .294 average and steady glove made him indispensable.

Toronto’s Isaac Montgomery (.347) and Montreal’s Robert “Buster” Brown (league-leading 15 triples and 9 homers) added offensive fireworks elsewhere, while on the mound the season turned into a duel between Excelsior ace Candy Lemmons and Pittsburgh’s Dennis Catchings. Lemmons, stolen from Rochester after 1881, led in ERA (2.06), while Catchings, a Vulcans lifer, topped the league with 38 wins.

Postseason Drama

With Rochester and Cleveland tied atop the Federal and the IA’s crown comfortably in New York’s hands, eyes turned to the Federal League tiebreaker. Unlike his predecessor, Federal League President Augustus Pembroke, who owned New York and had no stake in the pennant race, elected to add a single game to the slate, and allow the champion to be determined upon the field of battle.

The Rochester Robins romped over the Cleveland Blue Caps, 11–3, at Genesee Grounds. Jed Edwards led the charge, going 4-for-4 with a home run, a triple, two singles, and a walk. He crossed the plate four times and drove in a pair. The win secured the first pennant in club history for Rochester.

Bill Nolette earned his 29th win of the season, working all nine innings. He allowed seven hits and three runs while striking out four and walking two.

Larry Buckley gave Rochester a commanding lead with a grand slam in the bottom of the third. The first sacker finished 2-for-5 with a homer, a single, two runs scored, and four runs batted in.

“We’ve played well all season, so this is not a surprise to me,” said Pat Manke, the Robins’ player-manager, after the game. Manke, who already juggles duties as pitcher, catcher, and all around utility man, has added the manager’s chair to his growing list of responsibilities.

The IA, with no such playoff required, instead celebrated its first full season with a banquet in New York City, where Goodwin was feted in the press even as his fellow owners grumbled over his cutthroat ways.

A League in the Shadows

While the Federal and IA jostled for supremacy, whispers grew louder of a third circuit preparing for a debut in 1884. Bankers and industrialists in cities spurned by the existing leagues were said to be banding together, and former stars shut out of both loops were rumored to be in talks. Nothing had been finalized by winter’s end, but the possibility of another base ball war loomed large over the sport.

A New Face of Authority

In a shocking twist that no one saw coming, Pembroke resigned the Federal League presidency after the season concluded. He explained by saying that he wanted to focus on his team and now that peace between the Federal and International circuits had been achieved, he could no longer serve as President. His replacement, a non-baseball man, was lawyer-turned-banker Albert P. Whitford of Boston. A stern and serious man, Whitford's focus would solely on maintaining order and ensuring prosperity for the Federal League. Time would tell whether this step away from a "base ball man" at the top would be a smart move, or a failure.

- Details

- Category: Baseball

The Winter of 1883: A New Peace and Familiar Faces

The winter preceding the 1883 season marked a turning point in professional base ball. Following a single, acrimonious season of increased costs due to competition for players, the Federal and Interstate Leagues reached an accord. Dubbed the National Alliance of Professional Base Ball Clubs, the agreement called for mutual recognition of contracts, a reserve list of ten players per club in each league, and a universal blacklist — any player barred from one league would be excluded from all. The pact also noted the impending arrival of two regional circuits, scheduled to begin play in 1884, which would likewise be bound by the Alliance’s terms. For the first time, professional base ball could claim a measure of order across the country.

Federal League Franchise Shuffle

But peace at the league table did not mean stability in its ranks. In Philadelphia, old grudges had resurfaced. The Unions, expelled from the Federal League in 1878 after Henry C. Landis quarreled with then-president Charles W. Garrison, found their fortunes reversed. With Garrison now in his grave and his successor Augustus Pembroke unwilling to reopen old battles, the way was clear for Landis to buy his way back in. He purchased the Hartford Hawks and promptly uprooted them, re-establishing his beloved Philadelphia Unions as though they had never been gone. Hartford’s brief history would be absorbed, but its future was ceded to the City of Brotherly Love.

In Philadelphia, Henry C. Landis did not merely relaunch his old club — he gave the Unions a new home as well. After six years away from the big leagues, in a city that was hardly short on vacant lots and open fields, Landis secured a parcel along Girard Avenue and raised a handsome new wooden park, christened Girard Grounds. With space for some 5,000 spectators and easy access via the city’s expanding streetcar lines, the park offered a fitting stage for the reborn Unions, who now presented themselves not as upstarts but as rightful heirs to the city’s base ball tradition.

Providence, too, lost its nine, sinking in a sea of red ink. The rights to the Planters and their reserved players passed into the hands of Clinton Wood, one-time operator of the Detroit Woodward Base Ball Club. The eccentric Clinton Wood’s return to base ball came with a quirk only he could dream up. With the old Woodward Avenue Grounds long gone, Wood purchased land near the banks of the Detroit River and commissioned a new park, christened Riverside Park. The structure was a touch rustic — heavy timber, broad bleachers, and the scent of fresh-cut pine everywhere — but its location made it a natural gathering place for workingmen and fishermen alike. Befitting Wood’s newfound passion for angling, the club took the unlikely name of the Detroit Sturgeons, a moniker that raised eyebrows but quickly lodged itself in the city’s sporting vocabulary.

Amid these comings and goings, Chicago finally settled a matter long hanging in the air. With Harry Taylor now in control, he bowed to the wishes of his financiers and supporters by granting the club its popular sobriquet. The Chicago Cyclone Base Ball Club was at last official, its name registered with the League office in February. The Tribune celebrated with mock solemnity: “The tempest has at last a name, and it shall sweep from Lake Michigan across the diamond. Woe betide the unsteady nine who stand in its path.”

Thus, as the snow melted and the players made ready, the Federal League entered its eighth campaign with a fresh veneer of order — but also the familiar chaos of old rivals, old grudges, and new identities.

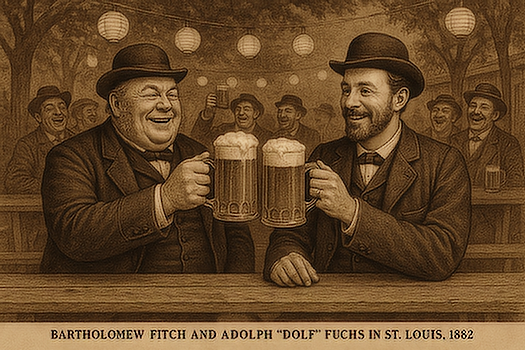

Interstate Association Expansion

The changes were by no means limited to the Federal circuit. With peace now secured, the International Association added two clubs to its ranks for its sophomore campaign. In what could be considered either a coup or a disaster, the IA admitted the legendary barnstorming club the Excelsiors of New York. Club operator Jeremiah Goodwin had spent five years stocking his club with top talent, and had earned the ire of many Federal League clubs along the way, as well as with fellow barnstormers such as Bartholomew Fitch and Dolph Fuchs. Fitch, putting business over (dis)pleasure, let Goodwin in for the "good of the circuit." Joining New York would be a new club in Indianapolis. Coming with far less fanfare - and expectations - the Indianapolis Stars brought the IA to a nice, round total of eight clubs.

The IA boldly grew to eight teams for 1883, adding two fresh entries:

-

New York Excelsiors: Reviving the proud name of one of the earliest base ball clubs, Jeremiah H. Goodwin placed his money and prestige behind the Excelsiors and built an independent base ball legend. Their home, Excelsior Grounds, was sited near the Harlem River and aimed to attract respectable crowds from uptown as well as diehards from Manhattan’s working wards.

-

Indianapolis Stars: The Hoosier State finally claimed its place in professional base ball. Amos L. Willoughby, newspaperman and publisher of the Indianapolis Evening Journal, erected a ground at the State Fair Grounds. Promoted heavily in print, the Stars expected to sparkle as a source of civic pride.

The IA’s expansion signaled the growing pull of base ball into both great metropolises and ambitious inland cities.

- Details

- Category: Baseball

The Federal League: 1882

“The Season of ’82”

If the business of 1882 was rocked by the death of Charles W. Garrison and the birth of the International Association, the game itself marched on. Cranks found plenty to cheer, jeer, and argue about as the season unfolded on both sides of the great Federal–International divide.

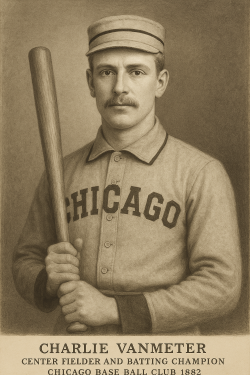

Federal League: Chicago Endures, Rochester Surprises

The Chicago Base Ball Club, now firmly under the control of Harry Taylor, weathered the storm of transition and emerged again atop the Federal League standings. Their 50–35 record was not dominant, but it was enough to stay clear of challengers from New York and Rochester.

The Chicago Base Ball Club, now firmly under the control of Harry Taylor, weathered the storm of transition and emerged again atop the Federal League standings. Their 50–35 record was not dominant, but it was enough to stay clear of challengers from New York and Rochester.

Chicago thrived on offense. Charlie Vanmeter repeated as batting champion with a .335 mark, Dick Sebastian muscled up with a league-best 15 home runs, and captain Morgan “Cap’n” Cook remained the glue of the lineup with his steady hitting and leadership at first base. On the mound, Doug Crockett (27–13, 2.53) shouldered the ace’s role, while Ben Brownfield (23–21, 2.87) kept the rotation afloat.

In New York, Tom “the Erie Eel” Ewart dazzled cranks with his all-around play. Slender and quick, he hit .300 with 23 doubles, 9 triples, and 9 homers, drove in 68, and scored 60. Even more remarkably, he started 11 games on the slab and went 7–4 with a sparkling 1.93 ERA. The Eel seemed to do everything at once, and Columbia Field buzzed with excitement whenever his name appeared in the box score.

The Rochester Robins, robbed of Dusty Trail by the lure of the International Association, nonetheless showed their mettle with a 46–38 campaign. Charlie Morris (.324) and Larry Buckley (.298, 7 HR, 64 RBI) powered the lineup, while pitchers Tom Bell (23–22, 2.63) and Woody Ross (17–10, 2.67) made the Robins the league’s second stingiest staff.

In Cleveland, disaster struck. The great Mike McCord, only 22, suffered a sore arm and managed just three mound wins before retreating to second base. Even there, he appeared a shadow of himself, hitting only .235 in 33 games. Whispers spread that the wonder boy of 1879 might be finished. Fortunately, “Black Jack” McKinley filled the void: the former Rochester ace snarled and scowled his way to a league-best 32 wins and a stingy 2.01 ERA, carrying the Blue Caps to a respectable but disappointing fourth-place finish.

The rest of the circuit offered little cheer. Louisville hovered at .500, Hartford faded, Providence and Milwaukee sank, leaving Rochester as the lone “small town” club to defy the odds.

Final Federal Standings, 1882

| Team | W | L | WPct | GB | R | RA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicago Base Ball Club | 50 | 35 | .588 | — | 459 | 385 |

| New York Columbians | 47 | 37 | .560 | 2½ | 461 | 401 |

| Rochester Robins | 46 | 38 | .548 | 3½ | 442 | 344 |

| Cleveland Blue Caps | 45 | 39 | .536 | 4½ | 386 | 340 |

| Louisville Colts | 42 | 42 | .500 | 7½ | 400 | 360 |

| Hartford Hawks | 39 | 45 | .464 | 10½ | 366 | 376 |

| Providence Planters | 35 | 50 | .412 | 15 | 370 | 490 |

| Milwaukee Creams | 34 | 52 | .395 | 16½ | 398 | 586 |

International Association: Toronto Strikes First

While the Federal League endured its own drama, the International Association completed its debut campaign with a pennant for Toronto. Owner Edmund B. Telford had promised to rub American noses in Canadian glory, and his Provincials obliged with a 44–36 record, a game and a half clear of the St. Louis Pilots.

Toronto rode the bat of 21-year-old Isaac Montgomery, a Boston native who won the batting crown at .330, and the surprising two-way play of Bill Silvers, a defector from Milwaukee. Silvers hit .294, led the club in RBI, and even pitched, going 13–5 with a 2.31 ERA in 18 starts. Fans at Dominion Field wondered why he wasn’t the ace instead of the erratic Henry Clancy.

The league’s brightest star was Albie Scott, a 21-year-old from Washington, D.C., who pitched for Cincinnati. Scott claimed the pitching “triple crown” with 29 wins, a 1.93 ERA, and 215 strikeouts, while piling up 470 innings. If not for weak support from his club, he might have carried the Monarchs to the flag.

Among the jumpers, Paul “Dusty” Trail batted .327 for Pittsburgh but languished on a last-place team, making Rochester fans in the Federal League wonder if he regretted leaving. Baltimore’s John Corbin (ex-Providence) posted a 2.05 ERA, while Montreal’s flashy second baseman John Clark brought style if not victories.

Final International Standings, 1882

| Team | W | L | WPct | GB | R | RA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto Provincials | 44 | 36 | .550 | — | 478 | 415 |

| St. Louis Pilots | 42 | 37 | .532 | 1½ | 357 | 337 |

| Baltimore Bannermen | 37 | 37 | .500 | 4 | 319 | 349 |

| Cincinnati Monarchs | 40 | 40 | .500 | 4 | 340 | 323 |

| Montreal Tigers | 38 | 42 | .475 | 6 | 340 | 370 |

| Pittsburgh Vulcans | 33 | 42 | .440 | 8½ | 318 | 358 |

Two Leagues, Two Stories

In its seventh year, the Federal League crowned yet another champion in Chicago, even as the absence of Garrison cast a long shadow. Meanwhile, the International Association proved that it could not only survive but flourish, luring stars, drawing cranks, and crowning Toronto as its first flag-bearer.

Base ball now had two great circuits, and the future promised conflict, competition, and perhaps calamity. For the first time, the game belonged to more than one league.

- Details

- Category: Baseball

The Federal League: 1882 Off the Field

“The Crisis of ’82”

The year 1882 opened with mourning and uncertainty. In March, Federal League President Charles W. Garrison died suddenly at the age of 46. The man who had willed the league into existence, expelled the weak, and imposed order on chaos was gone. His passing left two enormous questions: who would steer the Chicago Base Ball Club, and who would guide the Federal League itself?

Succession in Chicago

In Chicago, the answer came swiftly. Former ace pitcher turned sporting goods magnate Harry Taylor assumed ownership of the Base Ball Club. Taylor had already served as Garrison’s trusted lieutenant, both as a vice-president of the club and the man who had discovered and signed young Doug Crockett. To the cranks, the transition felt natural: the Cyclones would remain in the hands of a stern, ambitious man who understood both the playing field and the ledger.

Yet Taylor’s ambitions stretched beyond the diamond. His Taylor’s Sporting Goods Company was already spreading bats, balls, and uniforms across the country. As his empire grew, so too did his influence in the business of the game.

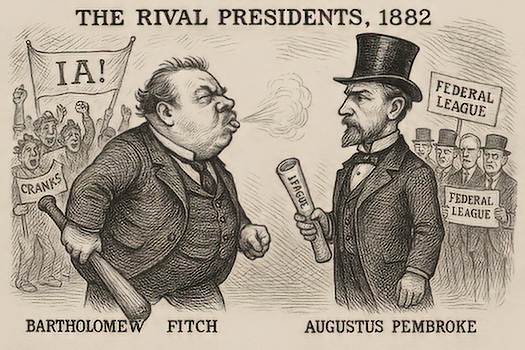

A New Federal President

The larger question lay in the presidency of the Federal League itself. For six years, Garrison had been judge, jury, and executioner — not always fairly, but always decisively. Without him, the league risked splintering.

After weeks of wrangling, the owners elected Augustus Pembroke of New York as the new President. Pembroke, one of the league’s last surviving original magnates, had earned a reputation for cautious stewardship of the Columbians. His election was pragmatic: he was trusted, sober, and available. Yet many wondered if Pembroke had the iron will to follow Garrison. For now, stability mattered more than style.

Enter the International Association

Even as the Federal League adjusted to life after Garrison, a rival appeared. In April, the International Association announced itself as a six-club circuit determined to offer “base ball for the people.”

Even as the Federal League adjusted to life after Garrison, a rival appeared. In April, the International Association announced itself as a six-club circuit determined to offer “base ball for the people.”

Led by Bartholomew Fitch of Cincinnati — styling himself “President” of the IA as well as owner of the Monarchs — the new league offered cheaper tickets, looser contracts, and a promise of unbuttoned entertainment. For men like Fitch and Adolph “Dolf” Fuchs of St. Louis, expelled from the Federal years before, the IA was personal revenge.

The six IA clubs:

-

Cincinnati Monarchs – Bartholomew Fitch, Queen City Grounds.

-

St. Louis Pilots – Dolf Fuchs, Fuchs Park (beer garden intact).

-

Baltimore Bannermen – James T. Banner, Banner Field.

-

Montreal Tigers – Victor H. Leduc, St. Gabriel Grounds.

-

Pittsburgh Vulcans – Hiram P. Kilgore, Vulcan Grounds.

-

Toronto Provincials – Edmund B. Telford, Dominion Field.

The Canadian clubs gave the league its “International” flair, and Telford in Toronto openly boasted of showing the Americans “how base ball ought to be played.”

Jumping the Fence

The IA drew its rosters largely from minor league circuits, but it lured several headline names away from the Federal. Chief among them was rookie sensation Paul “Dusty” Trail, who spurned Rochester and signed with Pittsburgh, his adopted hometown. The cranks in western Pennsylvania celebrated his return as a local hero.

The IA drew its rosters largely from minor league circuits, but it lured several headline names away from the Federal. Chief among them was rookie sensation Paul “Dusty” Trail, who spurned Rochester and signed with Pittsburgh, his adopted hometown. The cranks in western Pennsylvania celebrated his return as a local hero.

Other jumpers included pitcher John Corbin (from Providence to Baltimore, where he would finish second in ERA) and flashy second baseman John Clark (leaving Boston for Montreal). Their defection highlighted a growing problem: the reserve clause.

Instituted by the Federal League in 1879 and increasingly enforced by ’82, the clause bound players to their clubs year after year, restricting their movement and holding down wages. For men like Trail, Clark, and Corbin, the IA offered freedom: higher pay, fewer restrictions, and a chance to escape the “ties that bind.”

Federal Resolve Tested

The Federal League dismissed the IA as a sideshow, but its very existence undermined the aura of control that Garrison had spent six years building. Cranks, meanwhile, delighted in the spectacle: a rivalry not just between clubs, but between leagues, owners, and philosophies of what base ball ought to be.

For the first time, the Federal League faced a competitor that looked more than temporary. The crisis of 1882 was not only Garrison’s death but the question of survival in a world where rival banners flew.

- Details

- Category: Baseball

The Federal League: 1881

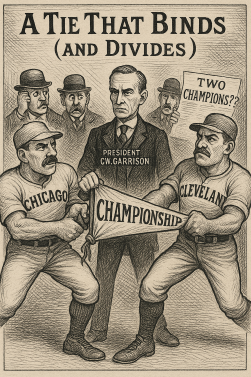

“A Tie That Binds (and Divides)”

By its sixth season, the Federal League had grown used to chaos. Teams changed names, players jumped contracts, and magnates feuded in smoke-filled rooms. But 1881 introduced something new: a pennant race so tight it ended in a dead heat.

The Tie at the Top

The Chicago Base Ball Club and the Cleveland Blue Caps finished locked at 55–28, their records identical down to the run columns. The two sides had split their season series, each claiming eight victories in sixteen meetings.

The Chicago Base Ball Club and the Cleveland Blue Caps finished locked at 55–28, their records identical down to the run columns. The two sides had split their season series, each claiming eight victories in sixteen meetings.

What followed was less a celebration than a governance crisis. As League President, Charles W. Garrison held the authority to decide the matter. As owner of Chicago, he also had everything to gain by breaking the tie in his own favor.

The newspapers howled about “a fox guarding the henhouse.” Some demanded a deciding series, others insisted on awarding the pennant to Cleveland on the grounds of superior run scoring (540 to 525). But Garrison, perhaps realizing that even he could not weather the storm of self-interest, declared both clubs co-champions. The precedent was awkward, the optics worse, but the tie stood.

A Dusty Trail Appears

If the boardroom was tangled in dispute, the field was graced with a new star. Paul “Dusty” Trail, a Scottish-born rookie with the Rochester Robins, electrified the league by batting .389 with 136 hits. Cranks quickly adopted him as their new darling, his easy swing and steady glove giving Rochester its first true gate attraction.

Behind him, familiar names filled the batting race. Chicago captain Morgan “Cap’n” Cook hit .358, proving that he was still one of the league’s premier hitters and baserunners. Cleveland catcher Bob Marshall followed at .355, his bat nearly as valuable as his defense.

Arms in Action

The mound was again a contest of giants. Cleveland’s Mike McCord posted 38 wins and a 2.67 ERA, cementing his reputation as the league’s steadiest workhorse. But the ERA title went to Louisville’s Ed Wales, whose 2.47 mark underscored his importance to the Colts’ surprising push into the first division.

New York, though fading in the standings, introduced an intriguing novelty in Tom Ewart. A true two-way man, Ewart hit .301 with 19 doubles, 7 triples, and 6 home runs, while also pitching to a 21–21, 3.08 ERA across 42 starts. He was, in short, the kind of all-around figure who belonged as much in dime novels as in box scores.

Final Standings, 1881

| Team | W | L | WPct | GB | R | RA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicago Base Ball Club | 55 | 28 | .663 | — | 525 | 375 |

| Cleveland Blue Caps | 55 | 28 | .663 | — | 540 | 369 |

| Rochester Robins | 44 | 39 | .530 | 11 | 468 | 454 |

| Louisville Colts | 44 | 41 | .518 | 12 | 426 | 385 |

| New York Columbians | 40 | 45 | .471 | 16 | 411 | 435 |

| Providence Planters | 39 | 46 | .459 | 17 | 412 | 489 |

| Milwaukee Creams | 32 | 52 | .381 | 23½ | 433 | 527 |

| Hartford Hawks | 27 | 57 | .321 | 28½ | 317 | 498 |

The Verdict

The year closed with two champions, one controversy, and one new star. To the cranks, the shared title was unsatisfying; to the owners, it was a reminder that governance mattered as much as base hits.

For Garrison, 1881 was a test of his authority. For Cleveland, it was a confirmation that their Blue Caps could match Chicago stride for stride. And for Rochester, it was the year a Dusty Trail led them out of obscurity.