The Federal League: 1882 Off the Field

“The Crisis of ’82”

The year 1882 opened with mourning and uncertainty. In March, Federal League President Charles W. Garrison died suddenly at the age of 46. The man who had willed the league into existence, expelled the weak, and imposed order on chaos was gone. His passing left two enormous questions: who would steer the Chicago Base Ball Club, and who would guide the Federal League itself?

Succession in Chicago

In Chicago, the answer came swiftly. Former ace pitcher turned sporting goods magnate Harry Taylor assumed ownership of the Base Ball Club. Taylor had already served as Garrison’s trusted lieutenant, both as a vice-president of the club and the man who had discovered and signed young Doug Crockett. To the cranks, the transition felt natural: the Cyclones would remain in the hands of a stern, ambitious man who understood both the playing field and the ledger.

Yet Taylor’s ambitions stretched beyond the diamond. His Taylor’s Sporting Goods Company was already spreading bats, balls, and uniforms across the country. As his empire grew, so too did his influence in the business of the game.

A New Federal President

The larger question lay in the presidency of the Federal League itself. For six years, Garrison had been judge, jury, and executioner — not always fairly, but always decisively. Without him, the league risked splintering.

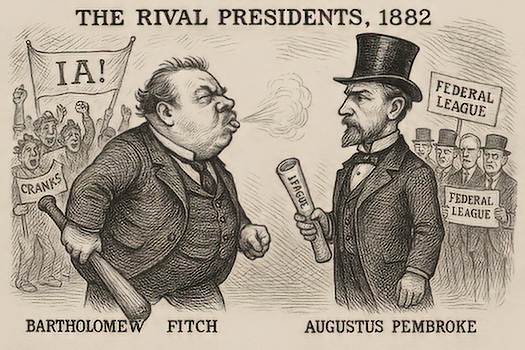

After weeks of wrangling, the owners elected Augustus Pembroke of New York as the new President. Pembroke, one of the league’s last surviving original magnates, had earned a reputation for cautious stewardship of the Columbians. His election was pragmatic: he was trusted, sober, and available. Yet many wondered if Pembroke had the iron will to follow Garrison. For now, stability mattered more than style.

Enter the International Association

Even as the Federal League adjusted to life after Garrison, a rival appeared. In April, the International Association announced itself as a six-club circuit determined to offer “base ball for the people.”

Even as the Federal League adjusted to life after Garrison, a rival appeared. In April, the International Association announced itself as a six-club circuit determined to offer “base ball for the people.”

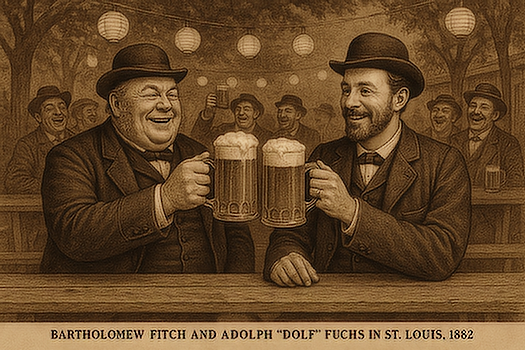

Led by Bartholomew Fitch of Cincinnati — styling himself “President” of the IA as well as owner of the Monarchs — the new league offered cheaper tickets, looser contracts, and a promise of unbuttoned entertainment. For men like Fitch and Adolph “Dolf” Fuchs of St. Louis, expelled from the Federal years before, the IA was personal revenge.

The six IA clubs:

-

Cincinnati Monarchs – Bartholomew Fitch, Queen City Grounds.

-

St. Louis Pilots – Dolf Fuchs, Fuchs Park (beer garden intact).

-

Baltimore Bannermen – James T. Banner, Banner Field.

-

Montreal Tigers – Victor H. Leduc, St. Gabriel Grounds.

-

Pittsburgh Vulcans – Hiram P. Kilgore, Vulcan Grounds.

-

Toronto Provincials – Edmund B. Telford, Dominion Field.

The Canadian clubs gave the league its “International” flair, and Telford in Toronto openly boasted of showing the Americans “how base ball ought to be played.”

Jumping the Fence

The IA drew its rosters largely from minor league circuits, but it lured several headline names away from the Federal. Chief among them was rookie sensation Paul “Dusty” Trail, who spurned Rochester and signed with Pittsburgh, his adopted hometown. The cranks in western Pennsylvania celebrated his return as a local hero.

The IA drew its rosters largely from minor league circuits, but it lured several headline names away from the Federal. Chief among them was rookie sensation Paul “Dusty” Trail, who spurned Rochester and signed with Pittsburgh, his adopted hometown. The cranks in western Pennsylvania celebrated his return as a local hero.

Other jumpers included pitcher John Corbin (from Providence to Baltimore, where he would finish second in ERA) and flashy second baseman John Clark (leaving Boston for Montreal). Their defection highlighted a growing problem: the reserve clause.

Instituted by the Federal League in 1879 and increasingly enforced by ’82, the clause bound players to their clubs year after year, restricting their movement and holding down wages. For men like Trail, Clark, and Corbin, the IA offered freedom: higher pay, fewer restrictions, and a chance to escape the “ties that bind.”

Federal Resolve Tested

The Federal League dismissed the IA as a sideshow, but its very existence undermined the aura of control that Garrison had spent six years building. Cranks, meanwhile, delighted in the spectacle: a rivalry not just between clubs, but between leagues, owners, and philosophies of what base ball ought to be.

For the first time, the Federal League faced a competitor that looked more than temporary. The crisis of 1882 was not only Garrison’s death but the question of survival in a world where rival banners flew.