1884 Season Recap

Federal League

Order held firm in the senior circuit, and the Blue Caps of Cleveland finally claimed the crown that had eluded them since 1879. Their talisman was pitcher Dan Hicks, whose season defied belief: 45 victories, a 2.01 ERA, and 363 strikeouts, good for the first true Pitching Triple Crown in Federal history. Hicks carried Cleveland to a 75–40 mark (.652), finishing comfortably ahead of New York and Philadelphia.

The bats were no less lively. Larry Buckley of Rochester seized the batting crown at .337 while driving in 96 runs and crossing the plate 113 times. Buckley’s blend of power (18 home runs) and consistency made him the most feared hitter in the league, though it was not enough to elevate the Robins beyond the middle of the pack.

New York’s Barons again found themselves bridesmaids, Philadelphia recovered from years of mediocrity, and Chicago’s Cyclones hovered near the first division. Detroit and Milwaukee sagged into the cellar, proving that even in a time of expansion and prosperity, not every market could sustain a winner.

Federal League Standings (1884)

| Team | W | L | Pct | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleveland Blue Caps | 75 | 40 | .652 | — |

| New York Barons | 70 | 45 | .609 | 5.0 |

| Philadelphia Unions | 63 | 52 | .548 | 12.0 |

| Chicago Cyclones | 58 | 50 | .537 | 13.5 |

| Rochester Robins | 56 | 59 | .487 | 19.0 |

| Louisville Colts | 48 | 66 | .421 | 26.5 |

| Detroit Sturgeons | 46 | 70 | .397 | 29.5 |

| Milwaukee Creams | 33 | 81 | .289 | 41.5 |

International Association

If Cleveland ruled the Federal, the IA’s banner went to St. Louis, where Adolph Fuchs’s Pilots soared to a 73–37 record (.664). Baltimore (70–38) pressed them all the way, but it was in St. Louis that fortune smiled longest.

The league’s batting laurels went to Curt Johnston of Baltimore, whose .353 average kept the Bannermen in the race. Yet the true thunder resided in New York: Jim “The Great Scot” Scott smashed 19 home runs and collected 107 runs batted in, both league highs, cementing the Excelsiors as the IA’s most glamorous draw.

Pitching honors were spread across the circuit. Albie Scott, having fled the collapsing National Alliance in midsummer, returned to his native Washington and promptly led the IA with a 1.81 ERA. Candy Lemmons of the Excelsiors won 40 games with a 1.82 ERA, while Indianapolis ace Stanley Lamb fanned 427, setting a strikeout standard that may endure for years.

Of the IA’s newcomers, Quebec and Toledo showed flashes of promise, while Washington’s Legislators and Boston’s Minutemen floundered badly, the latter propping up the table at 28–81. Still, the IA emerged stronger than it began, its footprint now stretching from the St. Lawrence to the Mississippi.

International Association Standings (1884)

| Team | W | L | Pct | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Louis Pilots | 73 | 37 | .664 | — |

| Baltimore Bannermen | 70 | 38 | .648 | 2.0 |

| Montreal Tigers | 69 | 40 | .633 | 3.5 |

| New York Excelsiors | 67 | 43 | .609 | 6.0 |

| Quebec Beavers | 57 | 51 | .528 | 15.0 |

| Pittsburgh Vulcans | 55 | 57 | .491 | 19.0 |

| Indianapolis Stars | 50 | 59 | .459 | 22.5 |

| Toledo Toms | 50 | 59 | .459 | 22.5 |

| Cincinnati Monarchs | 50 | 62 | .446 | 24.0 |

| Toronto Provincials | 39 | 70 | .358 | 33.5 |

| Washington Legislators | 38 | 72 | .345 | 35.0 |

| Boston Minutemen | 28 | 81 | .257 | 44.5 |

National Alliance

If the Federal and International Leagues embodied stability, the National Alliance proved the opposite. Formed with bluster and boasting eight clubs, it ended the year in tatters, reduced to six after Cincinnati folded on August 14 and Washington expired on September 1. The departures confirmed what many suspected from the outset: the Alliance was a house built on sand.

On the field, the one shining beacon was Boston, where the upstart Brahmins stormed to the pennant at 62–34 (.646). Their rookie ace Will James delivered one of the great debut campaigns in memory, winning 40 games while leading the league in strikeouts (458) and ERA (1.38). At the plate, Boston catcher Bob Marshall batted .351, led the league in home runs (12), and tied for the RBI crown with 55 — a rare feat of dominance at his position.

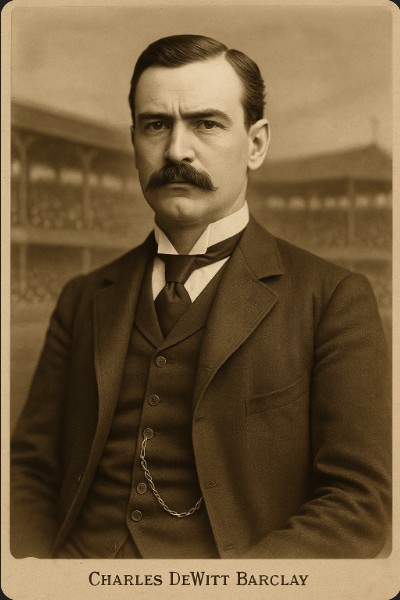

The league’s central drama, however, lay in St. Louis. Charles DeWitt Barclay, magnate, financier, and self-appointed NA President, stocked his Pioneers with stars lured from the wreckage of Washington in September. Even with the infusion of talent, the Pioneers fell short of Boston, finishing second at 55–37, but their outsized payroll and ambition ensured their survival. Already whispers circulated that Barclay’s club would not remain shackled to the flimsy Alliance.

Elsewhere, Philadelphia and Chicago muddled through, Baltimore drank more than it won, and Kansas City gamely pressed on despite financial woes. Cincinnati and Washington’s collapses sent many of their players scattering into the Federal and International circuits, further undermining the NA’s credibility. By season’s end, the Brahmins were champions in name, but it was clear the experiment had failed.

National Alliance Standings (1884)

| Team | W | L | Pct | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston Brahmins | 62 | 34 | .646 | — |

| St. Louis Pioneers | 55 | 37 | .580 | 7.0 |

| Philadelphia Bells | 45 | 48 | .484 | 17.5 |

| Chicago Catamounts | 51 | 46 | .526 | 11.5 |

| Baltimore Cannons | 42 | 49 | .461 | 19.5 |

| Kansas City Bulls | 41 | 45 | .477 | 18.0 |

| Washington Columbians | 33 | 48 | .407 | — folded Sept 1 |

| Cincinnati Dutchmen | 16 | 50 | .242 | — folded Aug 14 |

Keeping the Stove Hot

The winter of 1884 opened with more questions than answers. The National Alliance had plainly collapsed, its flimsy structure undone by unpaid wages, folding clubs, and a credibility gap too wide to bridge. Yet whispers abounded that not every Alliance nine would vanish into history.

The St. Louis Pioneers, flush with Charles DeWitt Barclay’s money and ambition, seemed destined for survival. Whether they would march straight into the Federal League, or attempt to cobble together a new circuit, remained the subject of endless speculation. Across the country, rumors swirled that the Boston Brahmins, champions in the Alliance’s only season, might yet find a home as well. Some claimed they would replace the feeble Boston Minutemen in the International Association; others thought their future tied to Barclay’s designs.

The IA itself faced hard choices. Twelve clubs had proven too many, diluting both talent and public enthusiasm. Crowds dwindled in smaller cities, and even the success of Baltimore and St. Louis could not mask the weakness elsewhere. Contraction back to eight seemed likely, but the question of who would survive the cut was left hanging in the winter air. Would Quebec be spared? Would Washington’s brief experiment be allowed to continue? Could Toledo and Indianapolis justify their places? None could say for certain.

Only one truth seemed beyond dispute: the National Alliance was finished. What form the great game would take in 1885, and who would be left standing to contest it, was left to rumor, ambition, and the turning of the new year.